The Early Years of the Mill

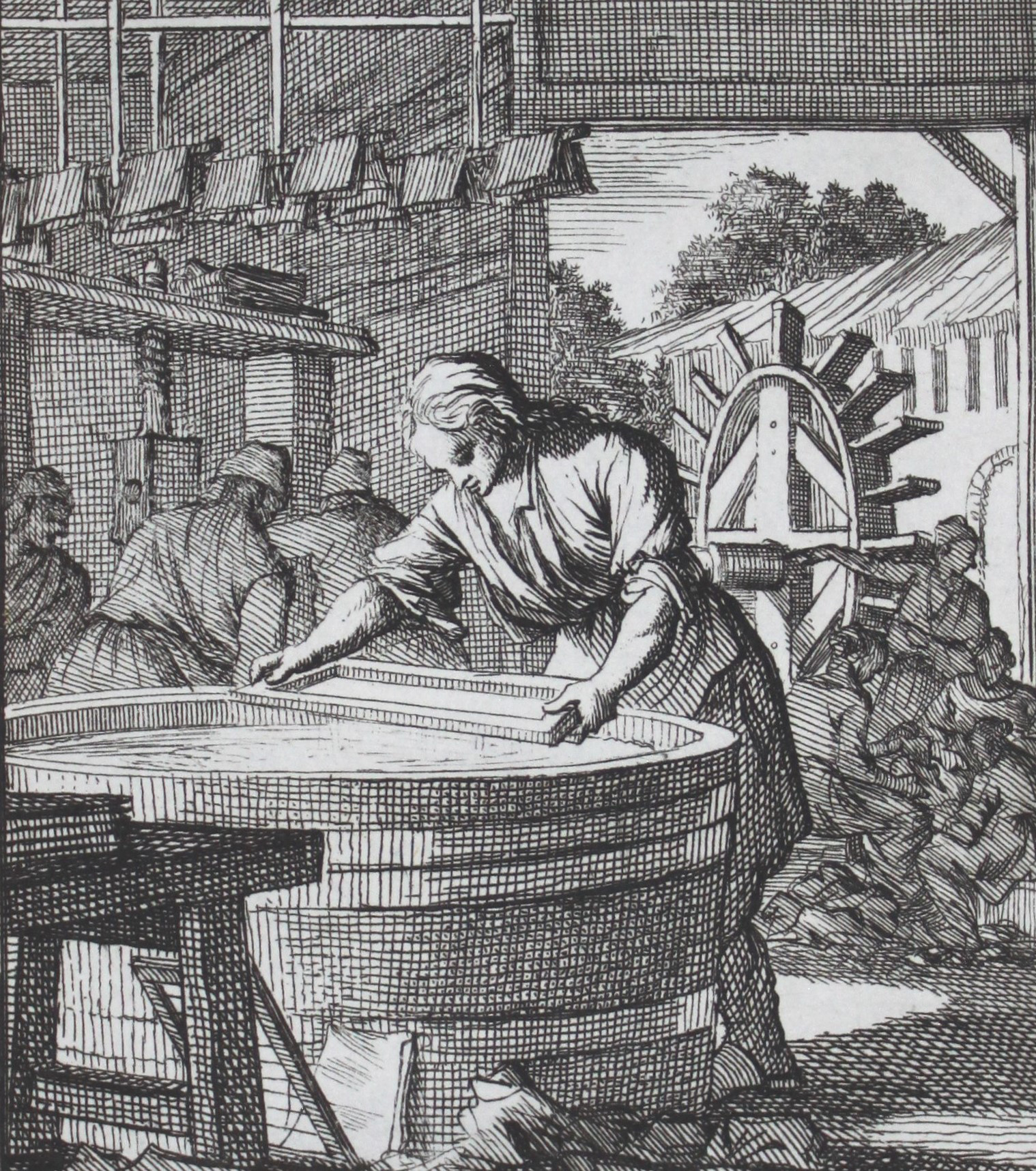

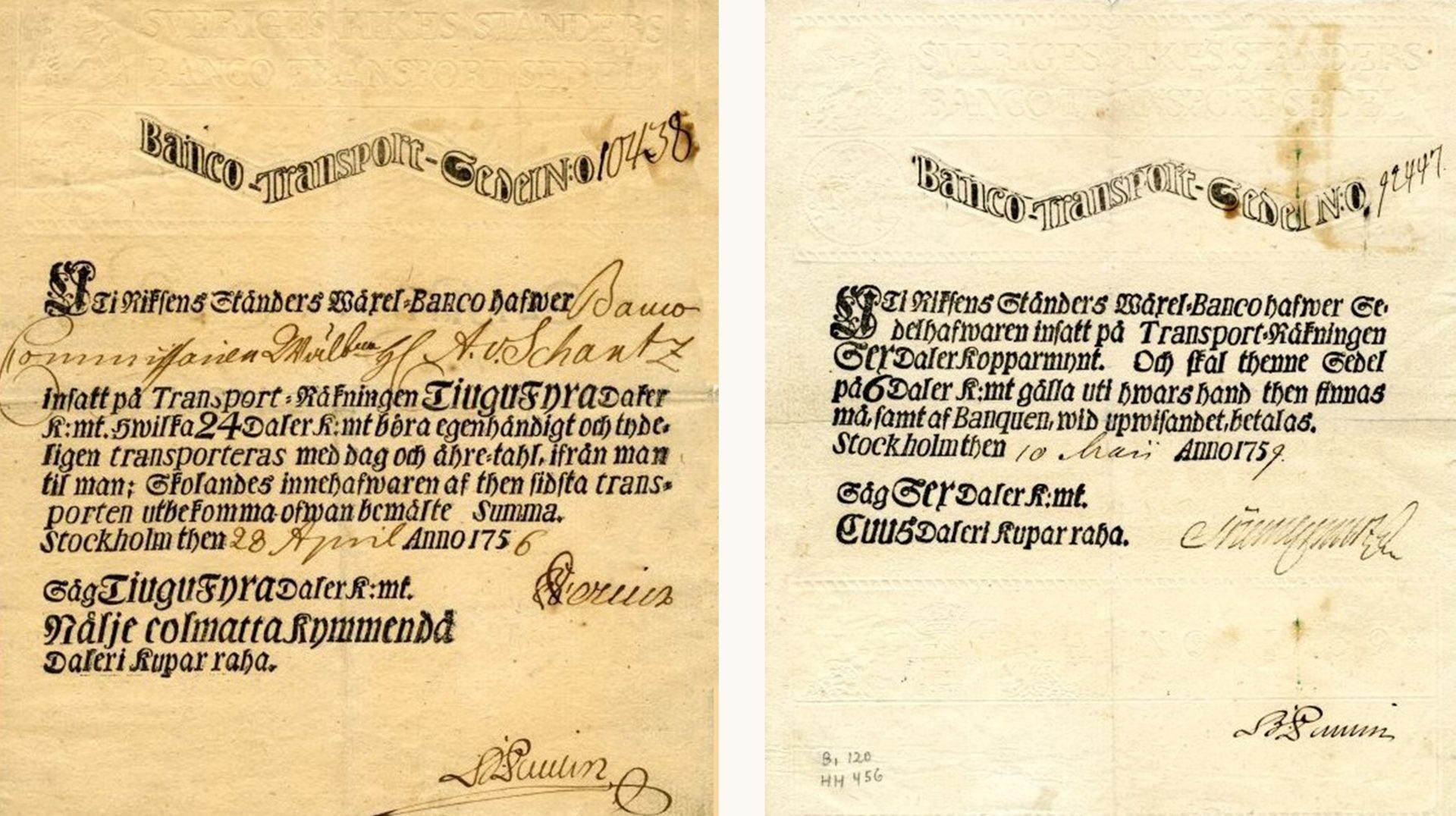

However, it became clear that the Swedish papermakers could make paper suitable for books, but not for banknotes. The Riksbank Board therefore decided to try to attract a Dutch master papermaker to move to Tumba. But the Dutch authorities did not want the knowledge of papermaking to spread under any circumstances. Finally, after negotiations through discreet agents, two brothers were persuaded to move: Jan and Erasmus Mulder.

Unfortunately, Jan Mulder spoke a little too openly about his plans to move, which led to his imprisonment. After a short period in prison, he died. This left Erasmus Mulder and his wife, who were secretly and stealthily brought to Sweden. A third brother, Caspar Mulder, made his way to Sweden a few years later to help.

Not good enough

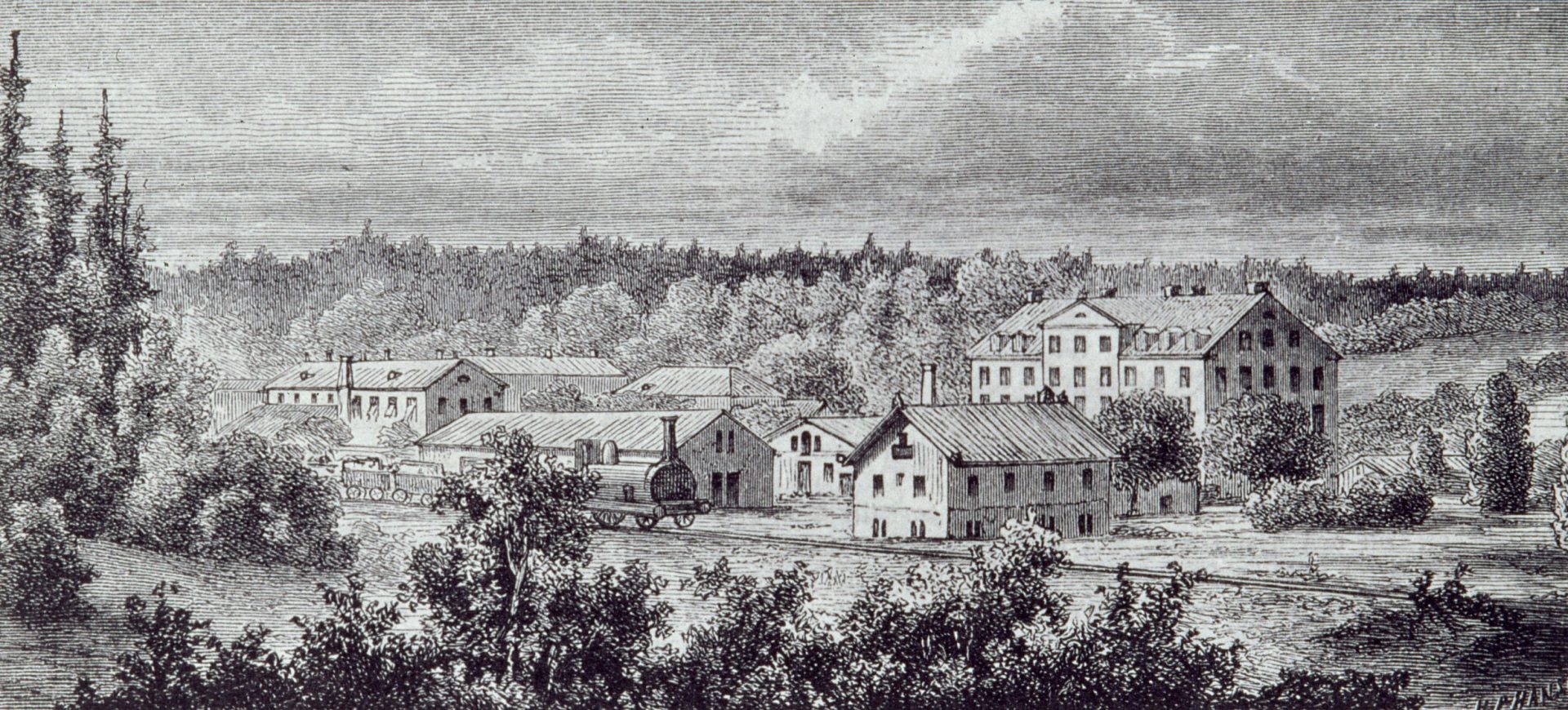

On arrival in Tumba, Erasmus Mulder found that the facilities Joakim Teuchler so proudly conveyed were not as good as he had wished. Relations between Teuchler and Mulder then became so strained that the Riksbank Board felt compelled to hire another site manager, Peter Momma, who was also of Dutch descent.

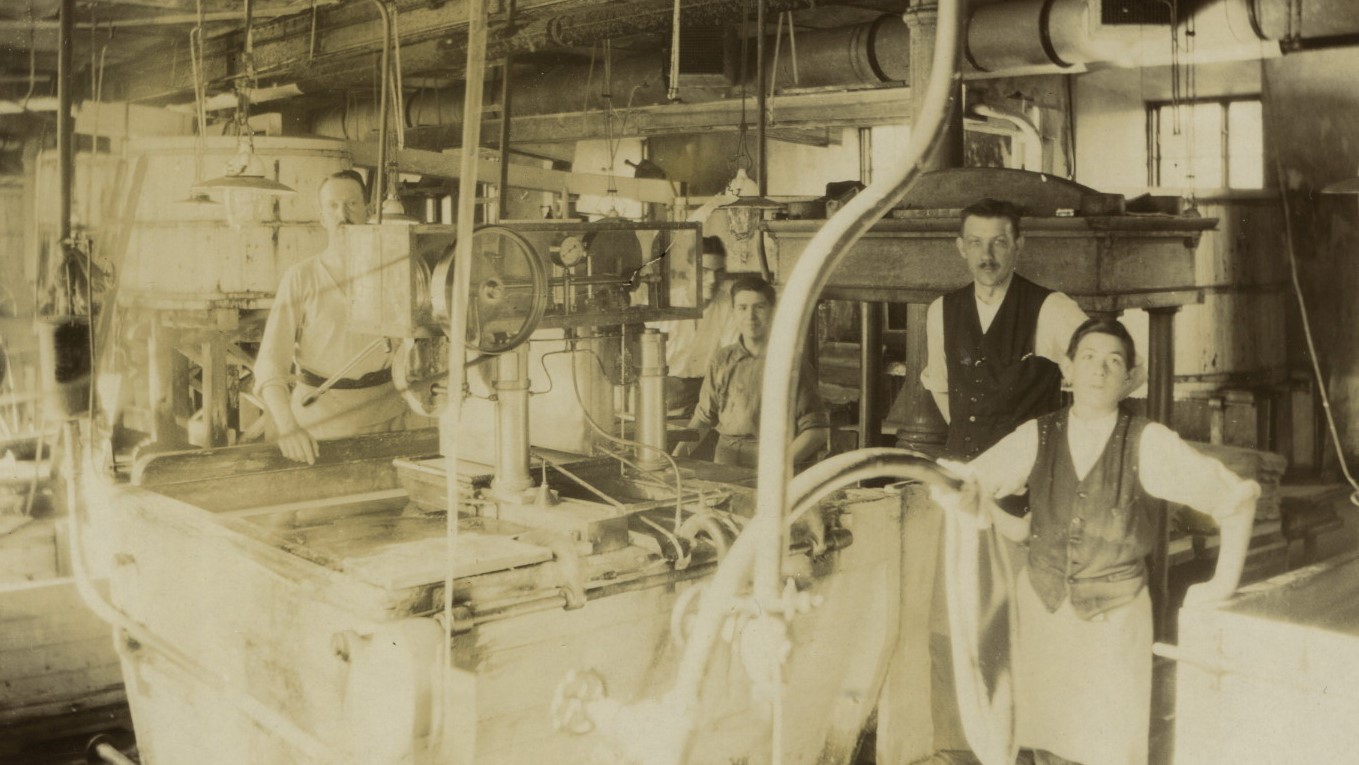

Initially, sixteen people worked directly on paper production. This increased to twenty-eight within a few years. These workers had families, and there were also crofters, tenant-farmers and others in the area. In 1759, the mill opened a little canteen, which was run by Christina Östberg. She was given the task of keeping the unmarried workers fed, selling groceries to the mill people, doing the washing, and caring for the sick when necessary. And to cook a good meal for the Riksbank members if they came to visit.

Ownership issues

Peter Momma succeeded in creating good cooperation between employers and employees, albeit at a greater cost than the Riksbank Board had wished. The Dutch knew what they were worth and Momma wanted to keep them happy. The paper mill delivered perfectly good banknote paper, but at a loss.

Already in the 1760s, the business was doing badly financially. It was also a time of crisis and high inflation. The crisis forced the mill to sell groceries to the workers at a discounted price, and the Riksbank Board considered privatising the paper mill. The argument against privatisation, which Peter Momma also stressed, was that security would be lost. A private owner could move or take the knowledge to another country. And a private owner might be tempted to produce their own banknotes. The mill remained state-owned.