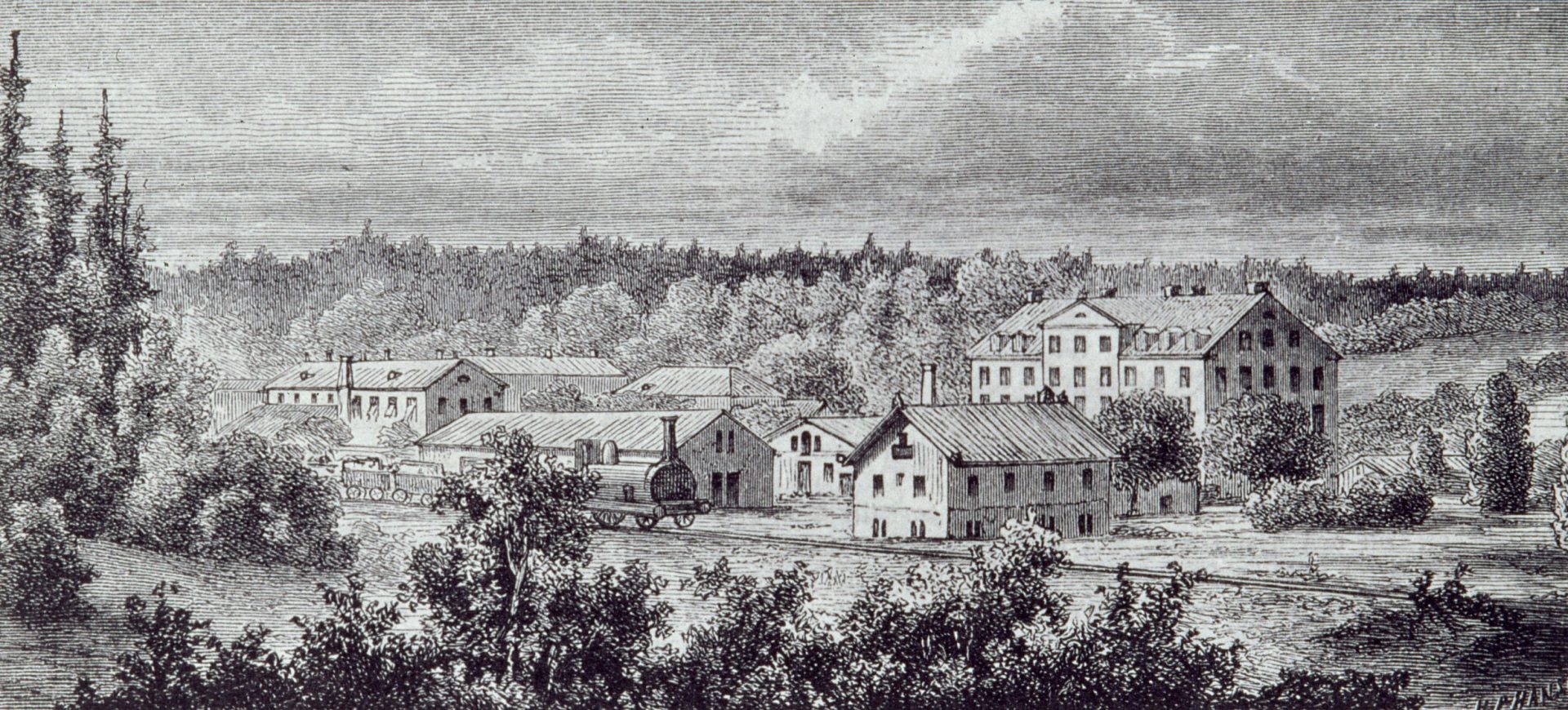

Modernisation of the Mill

Fiebelkorn was strongly conservative and opposed major changes in both working methods and labour law. Despite this – or perhaps because of it – the mill improved the quality of the paper during Fiebelkorn's time.

Major improvements to the mill, work and conditions in general came with his successor Johannes Vestergren: new worker housing, new mill buildings, electric light and even a provision for six days of holiday for all workers. In 1919, eight-hour days were introduced at the mill. And in 1925, a lorry replaced the old oxen to transport the fibre material used to make the paper. The pace of expansion meant that by 1930 there were more than 100 workers at the mill, plus about 70 apprentices and female workers.

Why make it by hand?

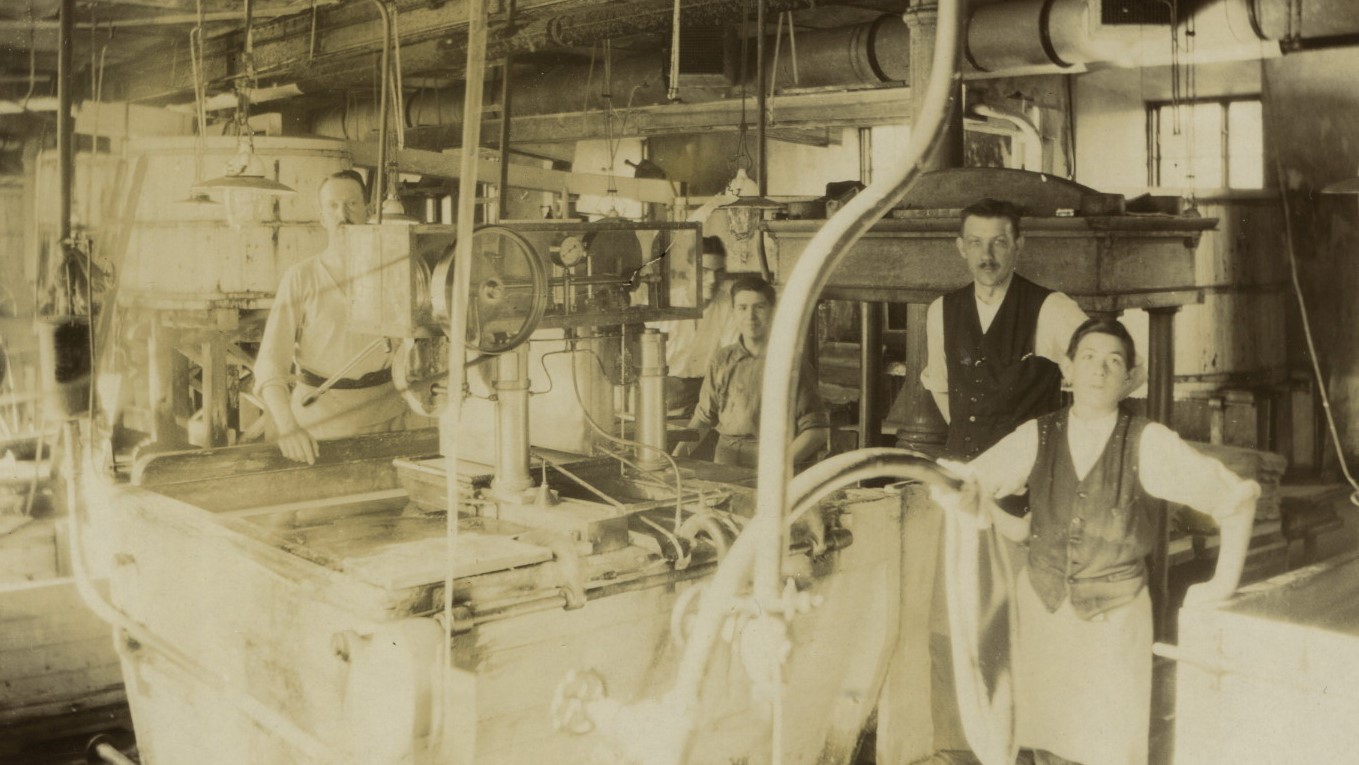

The progress was clear. So was the never-ending problem of the mill's profitability. Tumba's banknote paper was considerably more expensive than foreign equivalents. One of the reasons was that the paper was mainly produced in the same way as in the 18th century, by hand.

In 1934, the Riksbank's auditors stressed that the mill must acquire a paper machine to reduce costs. The auditors sent a copy of the report to the Riksdag, which prompted the Riksbank to act more quickly than usual. Five years later, the first machine was installed.

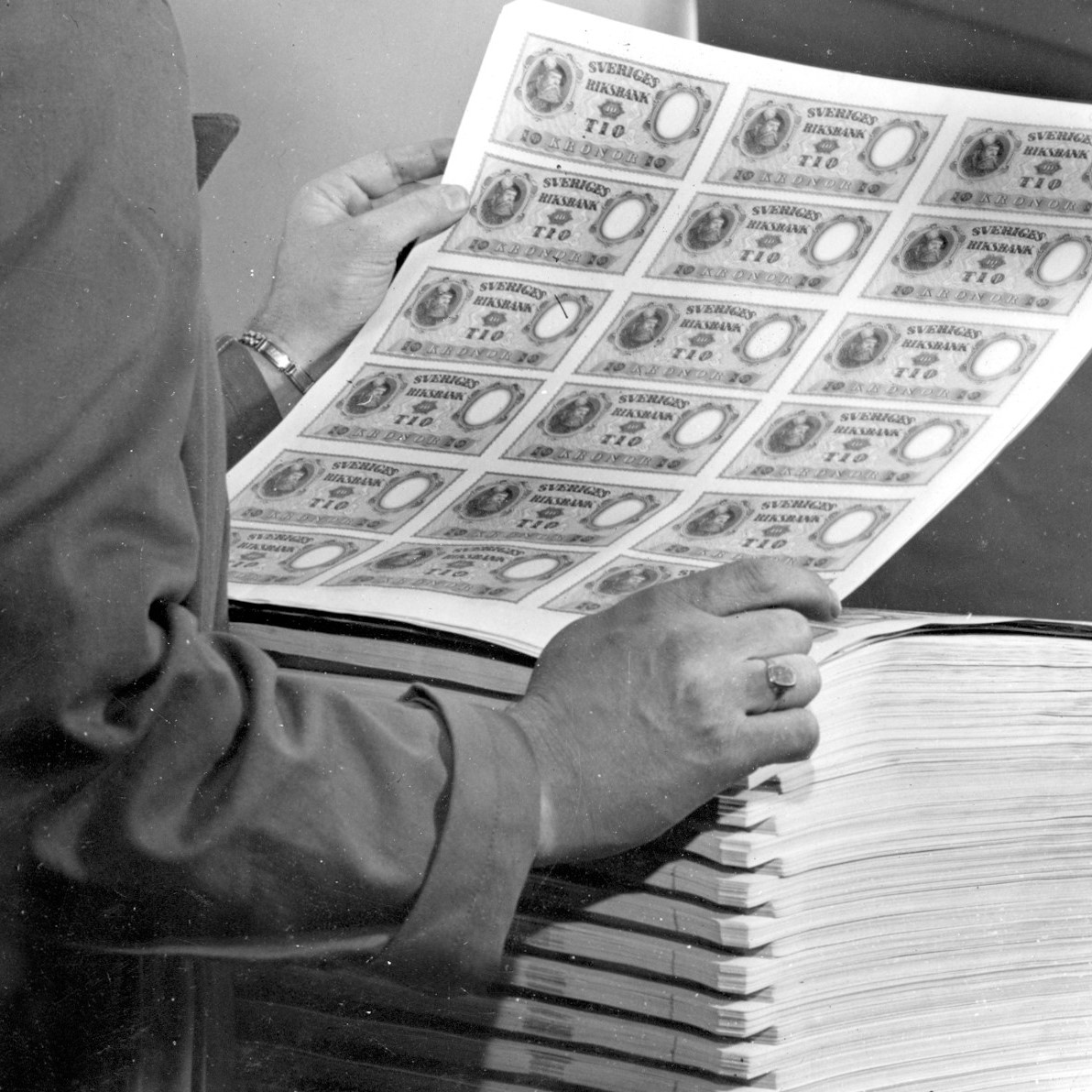

Engineers and fitters from Germany arrived in Sweden in August 1939 to install the paper machine from the Escher Wyss company. They barely finished before World War II broke out and they had to return to their homeland to fight in the war. In 1940, the first Swedish-produced machine-made banknotes were issued, a ten-crown note.

Reorganisation

The transformation of the mill took place at the same time as many of the papermakers retired and were replaced by younger, industrially trained workers. And now, after almost two hundred years, there was hope that the Tumba Paper Mill would turn a profit.

In 1944, the mill also began producing paper for the general market. Until then, the mill had produced paper more or less exclusively for the state, with certain exceptions such as banknote paper for private banknotes, paper for share certificates, and the like. Now, for the first time, the mill produced stationery, writing paper and fine art paper. The aim was to make better use of the capacity of the paper machine when there was a lull in orders for banknote paper.