Expansion of the Mill

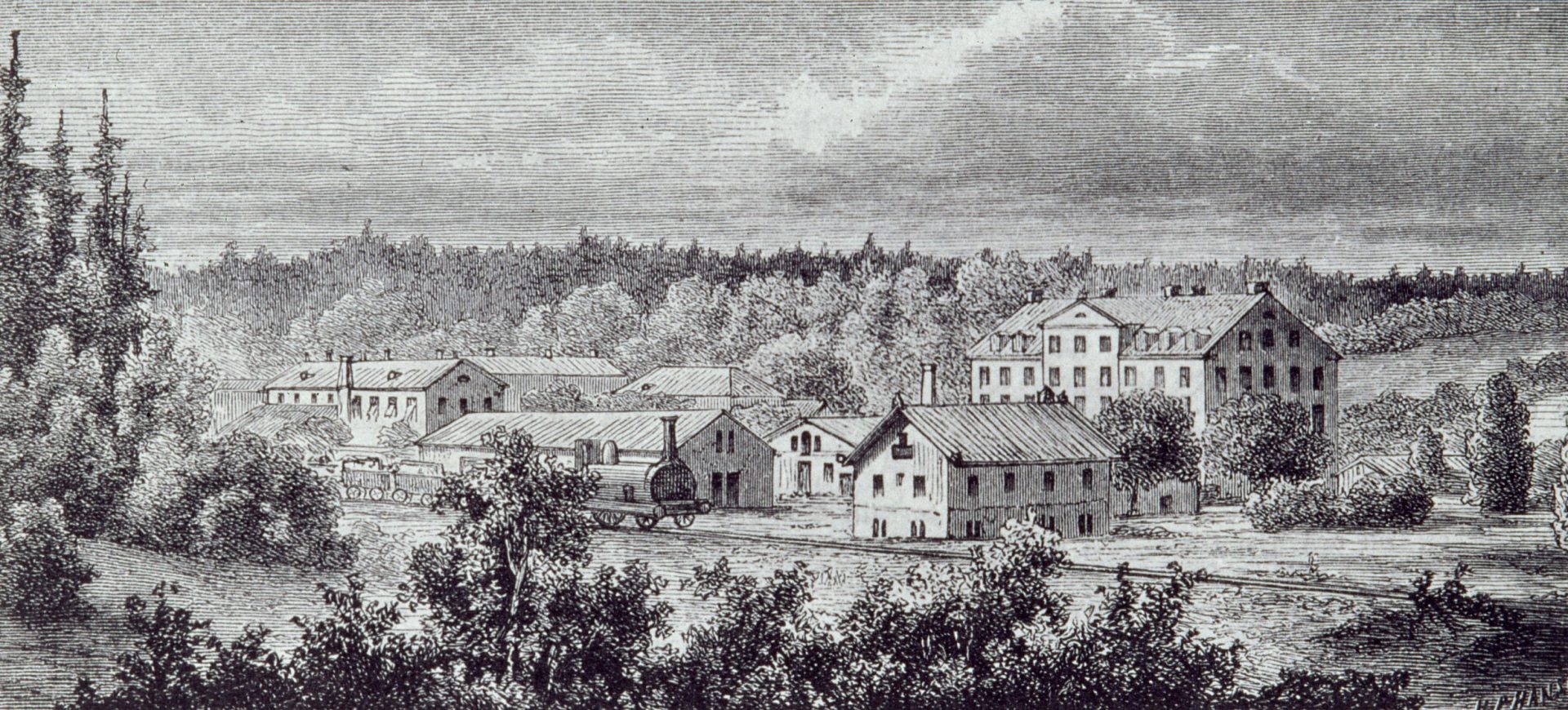

The mill's economy was slightly improved by the fact that many government offices ordered paper from Tumba. But the mill's production took a major blow when the old mill building burned down in 1829.

The mill rose again from the devastation. A new paper mill was followed by new worker housing and some modernisation of the almost fifty-year-old mill.

New banknotes

The major transformation in manufacturing took place in the 1830s. This was partly due to doubts about the security of Swedish banknotes and partly to the fact that the country's private banks were given the right to issue banknotes in 1831. The idea behind spreading banknote issuance was to free Swedish trade from state influence, which was in line with the desire at that time to change the antiquated and rigid class society. There were at most 26 banks issuing banknotes.

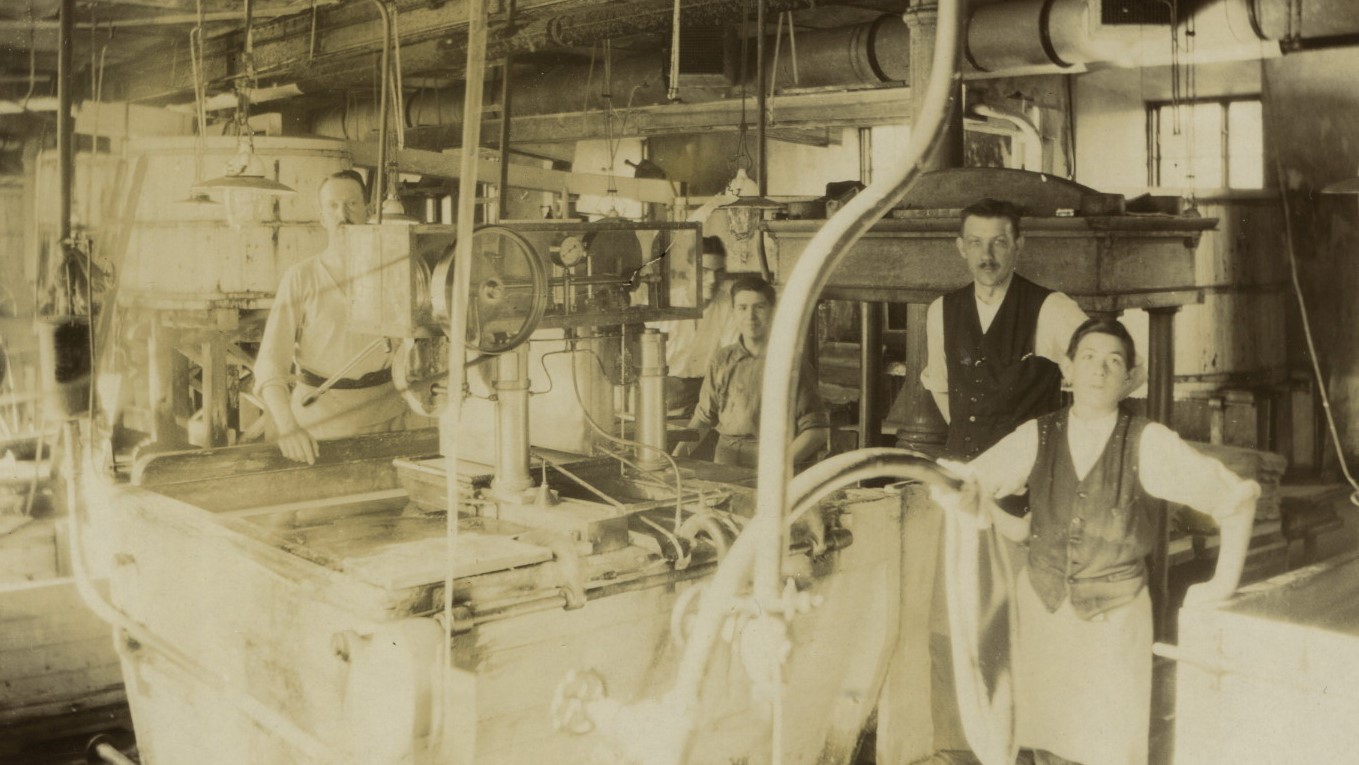

Unfortunately, the old banknotes were easy to copy. Some foreign banks had both thinner and better paper. Some also used coloured paper and more complicated printing methods. The difficulty was to create something similar. Jonas Bagge, the foreman, and Joakim Åkerman, a professor of chemical technology, set out to make a new type of paper with three layers, with the middle layer being coloured.

The process was complicated and time-consuming, but in the end the result was good. Each denomination was given its own individual colour, which increased security. In addition, the Riksbank Board decided that one or more of the bank's officials should be present during the production process to ensure full security. The banknotes came into use in 1836. The banknotes were given different nicknames due to their colours, such as the Canary.

And what about the profit?

The new banknotes required more water, so the water supply was improved with new channels and water cisterns. It seemed that the new-age paper mill was flourishing. But there were small worries on the horizon: the mill was still running at a loss, and free-trade advocates wanted to see it privatised.

The arguments for privatisation were that other countries' central banks rarely had their own mills, and that private mills could make paper that was just as good at a much lower cost. The arguments against privatisation were that the mill could hardly be sold at a profit, that security would be lost, and that the mill's other paper production for the state would then cease. Because the Riksbank Board was strong, and because one of the advocates of privatisation was Per Ambjörn Sparre, the previously dismissed manager of the Tumba Paper Mill, the mill remained in state ownership.

On the right track

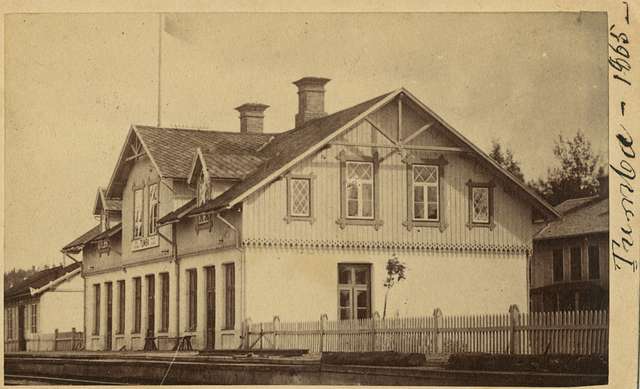

Modern times arrived in 1860 when Tumba was given a railway station on the Stockholm-Södertälje line. The following year, the mill installed its own gasworks to draw gaslight into the mill premises. Better light was necessary, as it had been noted that more sheets of paper were being scrapped after evening work or work during the dark winter months. In 1872, the workers were given a ten-hour working day.

Image, left: The railway at Smedjebacken, Ludvika, 1860. The Railway Museum. Top, right: Tumba station, 1865. Below, right: Tumba station, c. 1900. (Public Domain).

In 1897, the Riksdag (the Swedish parliament) decided that the Riksbank would have a monopoly on banknote issuance. Private banknote issuance ended in 1904, at the beginning of the era of democracy and revolutions.